Table of Contents

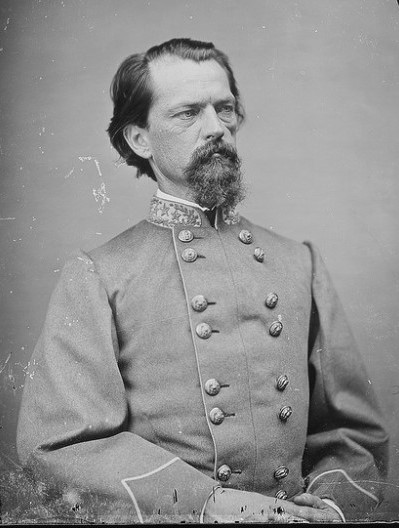

“You think I am going to die; but I am going to get well.”[1] John Brown Gordon’s statement to the Army physician after his wounding at the battle of Antietam might very well have been his lifelong motto.

A native of Georgia, Gordon joined the Confederate Army at the beginning of the Civil War and in May of 1862 was elected as colonel of the 6th Alabama Infantry. He and the regiment first “saw the elephant” at the battle of Seven Pines in June, where they were engaged in some of the hottest fighting. Although Gordon escaped being wounded at his first battle, his brother Augustus was severely wounded in the lungs.

Gordon and the 6th next saw action in July at the battles of Gaines Mill and Malvern Hill. At the latter, they came under severe artillery fire and Gordon described the effects of a shell exploding near him:

My pistol, on one side, had the handle torn off; my canteen, on the other, was pierced, emptying its contents—water merely—on my trousers; and my coat was ruined by having a portion of the front torn away . . . [2]

While he escaped injury from that particular shell, Gordon was not so lucky a while later:

A great shell fell, buried itself in the ground, and exploded near where I stood. It heaved the dirt over me, filling my face and ears and eyes with sand. I was literally blinded.[3]

Despite his fears of being permanently blind, Gordon was able to fully recuperate and regain his sight while his regiment was kept back in the defenses of Richmond after the Union retreat from the peninsula.

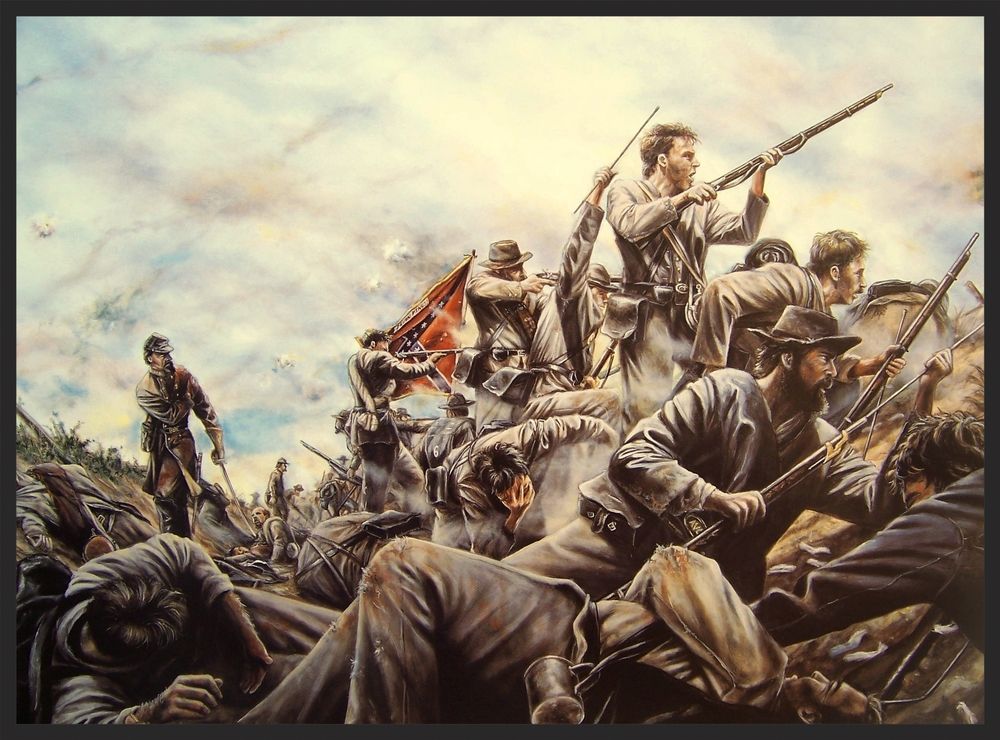

The fall of 1862 saw the Confederate forces moving north into Maryland. After a bloody fight on South Mountain, the army was pulled back to Sharpsburg, where General Robert E. Lee decided to make a stand. On September 17, 1862, Gordon and his regiment were assigned to the center of the line, defending a sunken road. He pledged to Lee that his men would hold the line “until the sun goes down or victory is won.”[4]

Having already fought in some furious battles and only suffering an injury to his eyes, Gordon confessed to feeling a certain invulnerability as he stood with his regiment awaiting the Union attack:

My extraordinary escapes from wounds in all the previous battles had made a deep impression upon my comrades as well as upon my own mind. So many had fallen at my side, so often had balls and shells pierced and torn my clothing, grazing my body without drawing a drop of blood, that a sort of blind faith possessed my men that I was not to be killed in battle. This belief was evidenced by their constantly repeated expressions: “They can’t hurt him.” “He’s as safe one place as another.” “He’s got a charmed life.” If I had allowed these expressions of my men to have any effect upon my mind the impression was quickly dissipated when the Sharpsburg storm came and the whizzing Minies, one after another, began to pierce my body.[5]

The first volley from Union troops sent a bullet through Gordon’s right calf. A short time later, he was hit higher up in the same leg, but no bones were broken, so he was able to continue walking along the firing line and encouraging his men. Another bullet ripped through his left arm, “tearing asunder the tendons and mangling the flesh,”[6] and causing blood to drip down his fingers. The soldiers, witnessing this, begged their colonel to go to the rear, but Gordon refused, stating that:

The surgeons were all busy at the field hospitals in the rear, and there was no way, therefore, of stanching the blood, but I had a vigorous constitution, and this was doing me good service.[7]

A fourth bullet then hit Gordon in the shoulder, leaving a fragment and wad of clothing in the wound. The shock and loss of blood began to take its toll, and Gordon struggled to remain on his feet. He was attempting to move to the right of his line to order his men to stand fast, when a fifth bullet struck him in the left cheek, passing out his neck and just missing the jugular vein. He fell forward face down into his cap, unconscious. He wrote of the experience:

It would seem that I might have been smothered by the blood running into my cap from this last wound but for the act of some Yankee, who, as if to save my life, had at a previous hour during the battle, shot a hole through the cap, which let the blood out. [8]

Gordon would later recall that it felt like the top of his head had been removed and that only part of his jaw and tongue were left.[9] He was taken on a litter to a field hospital, where he was revived with stimulants later in the evening. He found his surgeon at his side, and immediately asked what his prospects of survival were. Seeing the surgeon hesitate, Gordon replied, “You think I am going to die; but I am going to get well.”[10]

Gordon was evacuated from the battlefield and taken across the Potomac River to Virginia, where his wife was sent for. He was concerned that his appearance would frighten her:

My face was black and shapeless—so swollen that one eye was entirely hidden and the other nearly so. My right leg and left arm and shoulder were bandaged and propped with pillows.[11]

Indeed, his wife upon seeing him, had to stifle a scream, but after overcoming her initial shock, she never left his side, nursing him for several months. Because his jaw had to be wired shut, and because of the constant drainage from his wounds, Gordon was given brandy and beef tea to sustain him. When he developed erysipelas (a bacterial infection of the upper layer of the skin) in his left arm, the doctors told his wife to paint the arm three to four times a day with iodine. This was a lucky decision for Gordon. Most doctors during the Civil War were unaware of germ theory and did not understand the benefits of using antiseptics. Iodine was considered a remedy for a variety of ills but was not understood as an antiseptic. Gordon’s wife complied with the doctor’s instructions by applying the iodine, in Gordon’s estimate, three to four hundred times a day. He credited her treatment with saving not only his arm, but his life as well.[12]

By April of 1863, Gordon was able to return to duty, although his face was not yet totally healed. He had been promoted to brigadier general and he assumed command of Lawton’s Brigade. After fighting at Gettysburg and taking part in the Overland Campaign of 1864, Gordon was again wounded. As his brigade was withdrawing from Maryland after General Jubal Early’s unsuccessful attempt to take Washington, DC, Gordon was wounded over his right eye by an exploding artillery shell. Because he was in front of the skirmish line, Gordon turned his horse around and rode back to the rear, with the wound bleeding profusely. After having the wound dressed, he returned to the field after only 30 minutes.[13]

After Gen. Early’s defeat at Cedar Creek in October 1864, Gordon took command of the Second Corps of Lee’s army. He was tasked with defending the line during the siege of Petersburg and leading the attack on Fort Stedman on March 25, 1865. In retreating from the charge on the fort, Gordon was once again wounded—this time a flesh wound in his leg, which he described as not serious, and it did not force him to leave the field.[14]

Gordon would be present at the surrender of the Confederate Army at Appomattox on April 12, 1865. After the war he became a United States senator and later, the governor of Georgia. It must also be mentioned that he had been a slave owner prior to the war and perhaps a member of the Ku Klux Klan afterwards.[15] Despite his disturbing views on race and racial equality, there is no doubt that Gordon was an extremely tough and resilient man. After suffering eight wounds, Gordon surely would have died had he not been the lucky beneficiary of the early use of antiseptics and advanced medical care.

About the Author

Tracey McIntire earned her BA in English at Rivier College in Nashua, N.H. She is Director of Communications at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine and an active Civil War living historian, where she portrays a woman soldier in various guises. She is a historical interpreter at South Mountain State Battlefield and an interpretive volunteer at Antietam National Battlefield, where she met the great great granddaughter of General Gordon.

Endnotes

[1] Gordon, John B., Reminiscences of the Civil War, 1903, page 90

[2] Ibid., page 74

[3] Ibid., page 74

[4] National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/people/john-b-gordon.htm

[5] Gordon, John B., Reminiscences of the Civil War, page 88

[6] Ibid., page 89

[7] Ibid., page 89

[8] Ibid., page 90

[9] Welsh, Jack D., MD; Medical Histories of Confederate Generals, 1995, page 83

[10] Gordon, John B., Reminiscences of the Civil War, page 90

[11] Ibid., page 91

[12] Welsh, Jack D., MD; Medical Histories of Confederate Generals, page 83

[13] Ibid., page 83

[14] Gordon, John B., Reminiscences of the Civil War, page 411

[15] Eckert, Ralph Lowell; John Brown Gordon: Soldier, Southerner, American, 1993