Table of Contents

Museum members support scholarship like this.

“By Jingo, if you call this winter, I do not want to stay here in the summer,” exclaimed a soldier in the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Regiment shortly after his arrival at Key West for garrison duty in early February 1862.[1] The regiment, formed in the cold climes of Pennsylvania’s small towns, traded northern winter for Florida’s tropical weather. Immediately upon their deployment, this regiment battled heat and isolation, and their successors, particularly volunteers from New York, battled these hardships and the Civil War’s most deadly assailant: disease, specifically yellow fever, which raged at Key West during the summer of 1862. Given the military’s long history in Key West, the Civil War volunteers may have been aware that their duties could be threatened by this disease in addition to enemy bullets.

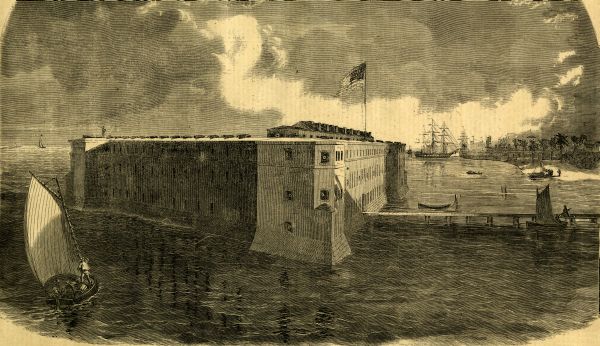

The United States’ acquisition of Florida in 1821 necessitated that U.S. Regular Army troops be stationed at Key West. This assignment subjected them to outbreaks of yellow fever. U.S. military officials recognized Key West’s strategic importance during the age of empire, when European nations possessed vast overseas territories and commerce largely relied on shipping. Almost immediately after Florida’s acquisition, Commodore David Porter acknowledged Key West as the “Gibraltar of the Gulf” and urged Congress to establish a full naval depot there since Spain and England had strengthened their side of the Gulf, while the U.S. remained vulnerable in the Gulf and South Atlantic.[2] The naval base came to fruition in 1823 and, in 1845, U.S. engineers began construction of Fort Taylor to fortify Key West against competing powers in the Caribbean who might try to encroach on American commercial interests at the confluence of the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico.

The engineers tasked with establishing a U.S. presence on Key West and with building Fort Taylor periodically battled yellow fever. Newspapers kept the mainland abreast on the disease’s toll and unknowingly foreshadowed the challenges that U.S. soldiers would face during the Civil War. In 1823, yellow fever forced Porter and his men to flee the island almost immediately after the Secretary of the Navy detailed them to establish a base of operations at Key West. Pleas for help from Washington went unanswered, and evacuation was the only safe option. Yellow fever struck again after construction of Fort Taylor commenced. Army engineers and Northern work crews suffered from a minor outbreak, and the tropical heat and humidity plagued the transplanted Yankees as they struggled to build the fort.[3]

Key West suffered yellow fever outbreaks again in 1854, 1856, and 1860, and one rumored outbreak in 1861.[4] The 1854 bout claimed the life of the U.S. engineer in charge of Fort Taylor’s construction, and the lives of seven men. In 1860, soldiers of the 2nd U.S. Artillery stationed at Key West heeded previous lessons and planned to evacuate to Indian Key should the outbreak become an epidemic.[5] Civil War soldiers were likely cognizant of the perils of life and work in the tropics but, upon deployment, men assigned to Key West experienced them first-hand. They cursed the heat, dreaded the prospect of suffering an inglorious death due to disease, and hoped that they could adapt – individually and as a group – to the tropical climate to reduce the prospect of succumbing to yellow fever’s wrath.

Key West, its heat, humidity, and unpredictable epidemics seemed impossible to tame. But by the time that the Civil War broke out, U.S. government and military officials, including Captain John M. Brannan and Colonel Joseph S. Morgan who oversaw martial law in Key West, understood that soldiers had to overcome these obstacles lest the island succumb to secessionist sentiment or actually fall into the hands of the Confederacy. The strategic value of Key West was simply too high – the island served as the headquarters of the East Gulf Blockading Squadron, which strangled Confederate commerce and supply lines, and secured the fractured nation against European powers in the Caribbean.

U.S. soldiers faced sub-par conditions in early 1862 when they arrived to enforce martial law, which was declared on May 10, 1861. One nameless correspondent of the New York Herald griped about Key West’s sanitary conditions a few weeks prior to the arrival of the 47th Pennsylvania, 90th New York, and 91st New York for garrison duty. “It is well known that yellow fever has prevailed here,” he penned, noting that the disease was “very fatal” even with the island’s small population, and feared that thousands of “unacclimated troops” would compound any outbreak. The correspondent demanded that the government take steps to clean up the island’s filth, which ranged from streets littered with orange peels, coconut shells, and garbage, to cattle roaming unrestricted, to pigpens in lower-class gardens, and pools of stagnant water, one of which was in front of the Marine Hospital.[6] Military authorities, in his opinion, had to act since the civil authorities ignored the problem, and the welfare of all the residents – and of the soldiers soon to arrive – was at stake.

General Brannan acted quickly to improve conditions. In late February 1862, he appointed Major William H. Gossler Provost Marshal of the island and the clean-up commenced. A New York Herald correspondent, perhaps the same man who highlighted Key West’s uncleanliness, rejoiced that the military officers began regular street cleaning, oversaw the elimination of pigpens and other “nuisances of like nature,” and made every effort to “render Key West attractive.” This work paid off and the Herald noted that afterwards “no fear of yellow fever or any other disease of like nature” existed among the population.[7]

Key West, however, was not entirely free from maladies. Many soldiers from the 90th New York Volunteers fell ill shortly after their arrival at Key West. Reverend J.G. Bass, the chaplain who tended to this regiment, noted that ailing soldiers in the hospital received aid from the Brooklyn Young Men’s Christian Association, from his ministry, and from surgeon Dr. E.S. Hoffman and his stewards, which allayed their homesickness and psychological distress.[8]

If only these men could have prevented future illness. After a summer that witnessed no deaths from yellow fever, the disease ravaged the 90th New York in October 1862. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, published in the home town from which many of the men hailed, blamed Florida’s climate for the regiment’s “fearful” mortality rate. The disease took a great toll on the army engineers at Fort Taylor. Most victims were almost totally unaccustomed to the tropics and could not overcome yellow fever.[9] As the war dragged on, these men, and others stationed at Key West, feared not only the prospects of a Confederate assault, but also the equally unpredictable prospects of disease, especially a yellow fever outbreak.

Soldiers of the 47th Pennsylvania, 90th and 91st New York received a meteorologically warm welcome upon arrival at Key West, but as time went on they experienced the cold hardships of war, as did their comrades in the main theaters of battle. Disease, after all, was an indiscriminate assailant no matter where soldiers were stationed and regardless of assignment.[10]

Want to learn more? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter to discover more stories from Civil War medicine!

Become a museum member and support our educational programs and research like this.

Footnotes

[1] The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (Brooklyn, N.Y.) Feb. 14, 1862, p. 2

[2] The U.S. acquired Florida from Spain through the Adams-Onis Treaty (1819), which went into effect in 1821. Louise V. White and Nora K. Smiley, History of Key West (St. Petersburg, Florida: Great Outdoors Publishing Co.), 16; Clayton D. Roth, Jr., “150 Years of Defense Activity at Key West, 1820-1970,” Tequesta No. 30 (1970), 37.

[3] Maureen Ogle, Key West: History of an Island of Dreams (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2003), 18 and 40-41.

[4] Ogle, Key West, 50; Jefferson B. Browne, Key West: The Old and the New. A Facsimile Reproduction of the 1912 Edition with Introduction and Index by E. Ashby Hammond. Bicentennial Floridiana Facsimile Series (Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 1973), 35; Times Picayune (New Orleans, L.A.) Aug. 1,1856, p. 1; The Daily Exchange (Baltimore, M.D.) July 1, 1861, p. 1; The Daily Exchange (Baltimore, M.D.) July 27, 1861, p. 1.

[5] The Tennessean (Nashville, T.N.) July 13, 1854, p. 3; The New York Times (New York, N.Y.) April 21, 1860, p. 1

[6] In 1860, Key West’s population was close to 3,000. Browne, Key West, 54; The New York Daily Herald (New York, N.Y.) Feb 14, 1862, p. 1-2.

[7] Gossler’s name may also be found spelled as Gausler. “Free Genealogy Biography of William H. Gausler, Pennsylvania Volunteer of the Civil War,” http://www.pacivilwar.com/bios/gausler-william.php. The New York Daily Herald (New York, N.Y.) March 6, 1862, p. 8.

[8] The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (Brooklyn, N.Y.) March 14, 1862, p. 2.

[9] The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (Brooklyn, N.Y.) Oct. 1, 1862, p. 2. The 47th PA Vols sailed for Hilton Head in mid-June 1862 and returned to Key West in December 1862. There were members of the 47th that stayed behind when the regiment sailed in June. Lewis G. Schmidt, A CW History of the 47th Regiment of PA Veteran Volunteers: “The Wrong Place at the Wrong Time,” 1st edition (Allentown, PA: Lewis G. Schmidt, 1986), 145-146.

[10] Approximately 224,580 Union soldiers and 164,000 Confederate soldiers died of disease. Ohio State University, Statistics on the Civil War and Medicine, https://ehistory.osu.edu/exhibitions/cwsurgeon/cwsurgeon/statistics.

About the Author

Angie Zombek is Assistant Professor of History at the University of North Carolina at Wilmington. She is the author of Penitentiaries, Punishment, & Military Prisons: Familiar Responses to an Extraordinary Crisis during the American Civil War (Kent State University Press, 2018), and is currently working on a manuscript entitled Stronghold of the Union: Key West Under Martial Law.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.